www.acpa.org

www.acpa.org

Quarter 3, 2016

11

b e l k n a p p l a c e

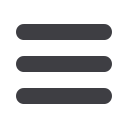

Close ups of the hand-scored

brick pattern added to provide a

foothold for horseshoes.

beginning of widespread adoption of the tech-

nology—with 2,963 miles constructed during

the year.

1

The construction of Belknap Place helped

contribute to that boon in concrete pavement

construction. Belknap Place was paved using

an innovative, patented process called Gran-

itoid, a two-lift system with coarse aggregate

in the lower lift and hard granite aggregate in

the surface course. The street has continued to

serve motorists well for more than a century,

with some natural cracking, but little faulting

or deterioration.

The surface aggregate and high quality of ce-

ment imparts excellent wearing characteristics,

according to Jan Prusinski, P.E., Executive Di-

rector of the Cement Council of Texas (CCT),

which took the lead in applying for the road’s

designation by the Texas Historical Commission

to underscore the significance of Belknap Place

to the concrete industry, local residents, and the

city of San Antonio. Prusinski also noted that

Don Taubert, Director of Promotion for Capitol

Cement (ret.), was instrumental in researching

and calling positive attention to Belknap Place.

Value was of great concern to early residents

whose homes lined Belknap Place, Prusinski said,

adding they split the cost of the road construction

with the city. “Concrete was more costly than

macadam or dirt, but city leaders and residents

wanted something special,” he explained. “The

road was built in less than three months, prob-

ably relying on hand and horse labor.”

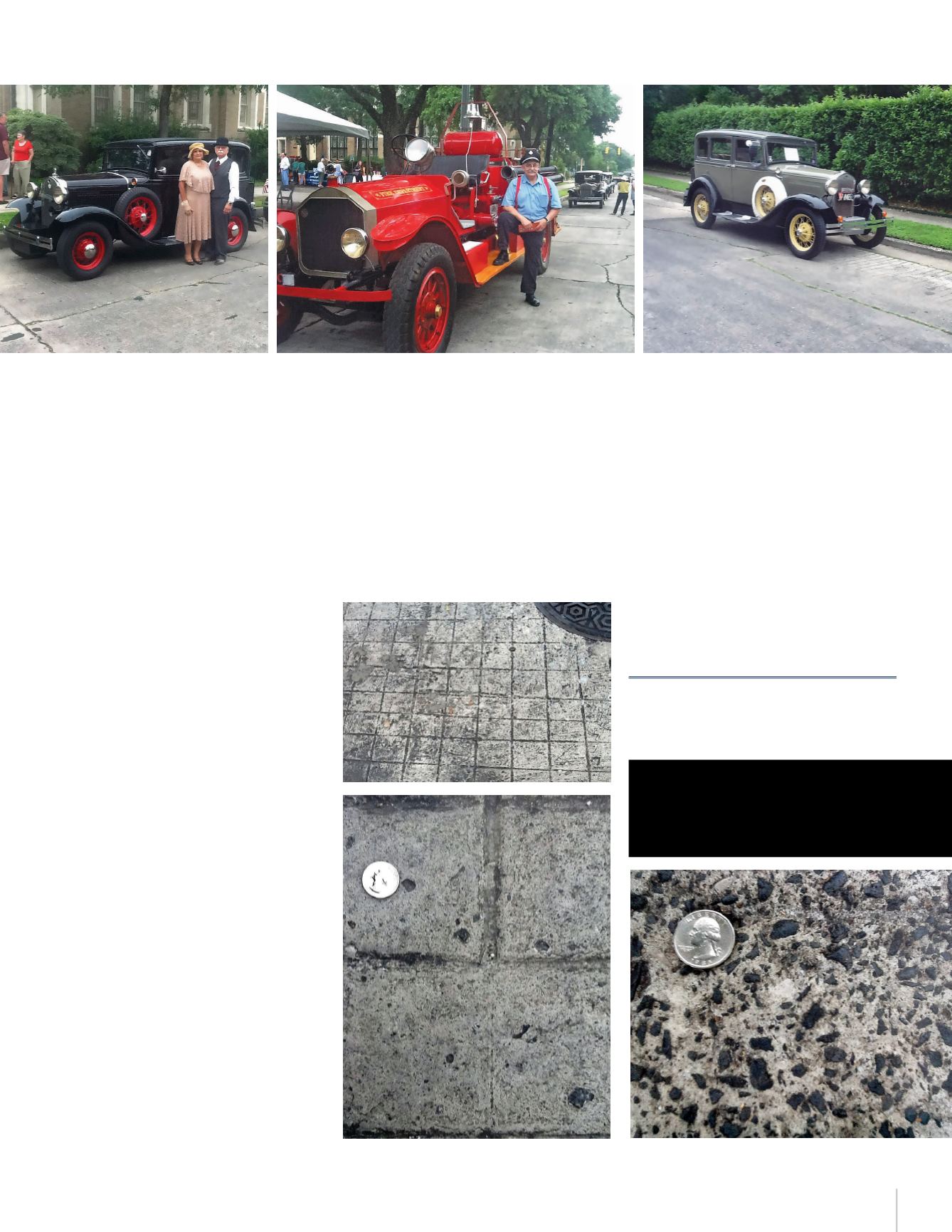

Key to the road’s durability is a dark indigenous

trap rock, according to Bill Ciggelakis, P.E.,

Professional Service Industries, Inc. He said

the stone is slowly cooled lava that is trapped

beneath the surface of the earth. It was likely

railed in from Knippa, Texas, located about 75

miles west of San Antonio.

The street was paved in 210 placements of 40-ft.

by 20-ft. sections, which were then brushed and

hand-scored in a 4 in. x 9 in. pattern to create a

brick pattern. The pattern provided a foothold

for the calks (toes or heels) of horseshoes—an

important consideration because horse and

carriage was the prevalent form of transporta-

tion in 1914.

Being home to the state’s oldest concrete pave-

ment makes sense because San Antonio is also

known as cement’s birthplace west of the Mis-

sissippi River, with the second oldest cement

plant in the nation, Prusinski said. “Alamo Ce-

ment’s original 1880 kiln and quarry still exist as

the Japanese Tea Garden, part of San Antonio’s

Brackenridge Park,” he explained. “The cement

for the Belknap Place concrete came fromAlamo

Cement’s second plant, built in 1908. Its smoke-

stacks now serve as the centerpiece of the Quarry

Market, an upscale, mixed-use retail, residential,

and golf community.” AlamoCement nowowned

by Buzzi USA, continues to operate a modern

plant in northeast San Antonio.

Reference

1. Portland Cement Association, “Facts Everyone Should

Know about Concrete Roads,” April 1916.