Tobacco Use Screening and Advice to Quit

By James Padilla

(Tobacco Use Prevention and Control (TUPAC) Program Epidemiologist),

Humphrey Costello and Jessica Roberts

(TUPAC Evaluators, Wyoming Survey & Analysis Center).

Introduction

Although the prevalence of cigarette smoking continues a

steady decline, it is still the leading preventable cause of death,

killing about 480,000 people in the U.S. and 2,600 in New

Mexico annually. One in five New Mexico adults still smoke

cigarettes, which is about 300,000 people. Most smokers want

to quit using tobacco but struggle in succeeding, often making

many attempts before quitting for good. Dental providers can

play an important role in their patients’ efforts in quitting to-

bacco, especially because many smokers see their dental care

providers regularly and there are risks for oral disease from

tobacco use.

According to the U.S. Public Health Service Guideline,

Treat-

ing Tobacco Use and Dependence

, there is strong evidence that

health care providers who deliver tobacco dependence treat-

ment (the 5As—Ask, Advise, Assess, Assist, Arrange) can pro-

duce significant and sustained reductions in patient tobacco

use.

1

The U.S. Health and Human Services

Healthy People

2020

, for the first time, included goals for improving tobacco

screening and cessation counseling in dental care settings.

2

Nationally, among smokers who saw a dental care provider

(dentist or hygienist), in the past year, about 12% reportedly

received advice to quit smoking (vs. 51% who reportedly re-

ceived this advice from a medical doctor).

3

Dental providers

were more likely to advise smokers who were male, aged 45-

64, non-Hispanic White, covered by insurance other than

Medicare or Medicaid, or smoked more than half a pack daily.

A separate national study of dentists showed that more than

90% of dentists reported routinely asking patients about to-

bacco use, that 76% counsel patients, and 45% routinely of-

fer cessation assistance (cessation counseling referral, prescrip-

tion, or both).

4

Provision of cessation assistance was more

likely to be reported among dentists who work in a practice

with one or more hygienists, have a chart system that includes

a tobacco use question, have received training on treating to-

bacco dependence, or have positive attitudes toward treating

tobacco use.

Methods

In Spring 2014, the Tobacco Use Prevention and Control

Program (TUPAC) in the NM Department of Health commis-

sioned a randomized telephone survey (n=1,035) that included

questions about a variety of tobacco-related topics, including

questions about whether people are asked about their tobacco

use by their health care providers. Smokers were also asked if

they are advised to quit by their health care providers.

The sample for the survey consisted of phone numbers drawn

from both cell phones and landlines, with an oversampling

of the cell numbers to ensure sufficient completions in hard-

to-reach populations of interest. For the landline sample, 159

surveys were completed for a 14.3% response rate. For the

cellular sample, 876 surveys were completed for a 10.7% re-

sponse rate. After the completion of the data collection, the

data were weighted so the results would be representative of

the NM adult population. The weight does not change a re-

spondent’s answers.

The researchers used Pearson’s chi-squared tests to assess

whether differences in outcomes across priority populations

were statistically significant with 95% confidence.

Results

Seeing a dental care provider

: Among NM adults, 63.4%

reportedly saw a dental care provider (dentist or dental hy-

gienist) in the past 12 months, and a similar number (63.3%)

reported seeing a doctor, nurse, physician assistant, or nurse

practitioner, which will hereafter be referred to as “other

health care providers.”

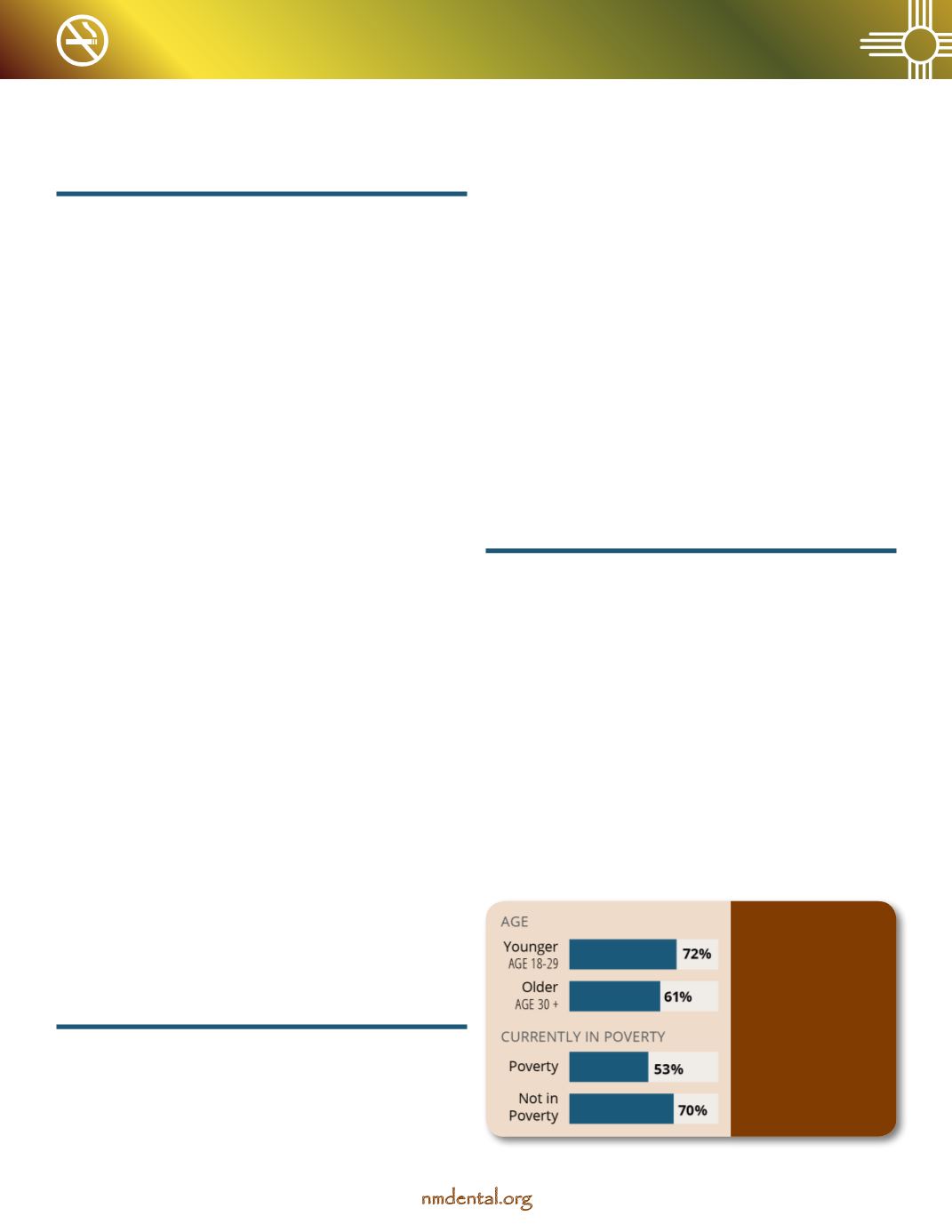

[Figure 1]

shows that young adults (18-29 years) were more

likely to have seen a dental care provider to get care in the past

12 months at 71.7%, compared to older adults (30 years+) at

60.6%. It also shows that adults currently experiencing pov-

erty were less likely to have seen a dental care provider in the

past 12 months (53.1%) compared to adults who were not

experiencing poverty (69.9%). No statistical differences in see-

ing a dental care provider were observed based on a respon-

dent’s ethnicity or race.

continues

7

nmdental.org

Figure 1

Adults who

were older or

experiencing

poverty were

less likely to

report seeing

a dental care

provider in the

past year.